The US Navy on Ocracoke

The United States involvement in

World War II started on December 7, 1941, and by January 18, 1942, the island people

suddenly became aware of the war when they were thrust into it by the sinking of the

tanker Allan Jackson, 60 miles off Cape Hatteras. Allied ships were lost due to German

U-Boats during March and April at the rate of about one per day along the Outer Banks in

the Graveyard of the Atlantic. The local people could hear explosions and see the flames

from the burning ships. The Diamond Shoals, sometimes called Torpedo Junction, was an

ideal shooting gallery for the German U-Boats to take out unprotected Allied and

American merchant vessels carrying supplies and tankers moving oil and gasoline. The

ships passing here were usually not in convoy and were easy prey for the waiting German

U-boats as they tried to go further offshore around the Diamond Shoals and the Navy mine

field. Those US Navy vessels remaining after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor were

preoccupied with protecting and moving convoys of ships carrying supplies and arms

overseas in both the Atlantic and Pacific to support the war effort on both fronts.

The United States involvement in

World War II started on December 7, 1941, and by January 18, 1942, the island people

suddenly became aware of the war when they were thrust into it by the sinking of the

tanker Allan Jackson, 60 miles off Cape Hatteras. Allied ships were lost due to German

U-Boats during March and April at the rate of about one per day along the Outer Banks in

the Graveyard of the Atlantic. The local people could hear explosions and see the flames

from the burning ships. The Diamond Shoals, sometimes called Torpedo Junction, was an

ideal shooting gallery for the German U-Boats to take out unprotected Allied and

American merchant vessels carrying supplies and tankers moving oil and gasoline. The

ships passing here were usually not in convoy and were easy prey for the waiting German

U-boats as they tried to go further offshore around the Diamond Shoals and the Navy mine

field. Those US Navy vessels remaining after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor were

preoccupied with protecting and moving convoys of ships carrying supplies and arms

overseas in both the Atlantic and Pacific to support the war effort on both fronts.

The people of Ocracoke and the

Outer Banks certainly had fears that the Germans would come ashore, but with their

normal Ocracoke and Banker attitude they were willing to accept whatever might happen.

Residents were told to black out and light that would escape through their windows at

night, and many used dark green window shades. Military security was established on the

island and enforced by the Navy and Coast Guard as they patrolled the beach on horse

back and guarded other key locations on foot. They kept people off the beach, especially

at night and never told the public what was going on, all operations were kept secret.

The local people were able to continue fishing and using their fishing and hunting camps

on the north end of the island.

The people of Ocracoke and the

Outer Banks certainly had fears that the Germans would come ashore, but with their

normal Ocracoke and Banker attitude they were willing to accept whatever might happen.

Residents were told to black out and light that would escape through their windows at

night, and many used dark green window shades. Military security was established on the

island and enforced by the Navy and Coast Guard as they patrolled the beach on horse

back and guarded other key locations on foot. They kept people off the beach, especially

at night and never told the public what was going on, all operations were kept secret.

The local people were able to continue fishing and using their fishing and hunting camps

on the north end of the island.

Ocracoke residents proved to be a great help to the survivors from the torpedoed vessels by providing clothes and other necessities for them after rescue. Most people never saw the survivors, who were housed on the Sound side of the new Coast Guard station in tar papered barracks until transported to the mainland. Many of the island families made room and rented space in their homes for Navy families to stay, some residents moved in with relatives and rented their entire house to the Navy families.

When the war started most of the local men were away working in Philadelphia, Baltimore or Norfolk on the US Army Corps of Engineers dredges, with other dredging companies or in maritime merchant ships. Many other men who were still on Ocracoke enlisted or were drafted, some were already in the US Coast Guard serving in various locations around the world when the war started.

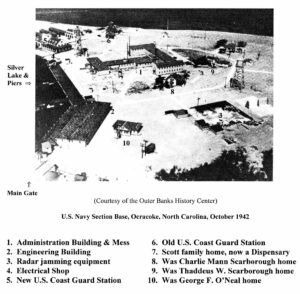

Early in the war the US Navy had very few warships available to protect shipping except for those in major overseas convoys. Preparations were made to build a US Navy Section Base on Ocracoke. Several families who had homes and owned land in the vicinity of the Coast Guard Stations were forced to sell their property.

The US Navy Base was constructed

in the area around the Coast Guard Stations in the village and was started in May or

June 1942. The Base was commissioned on October 9, 1942. The creek needed to be dredged

for use by the Navy while building the Navy Section Base. Some of the sand was used to

fill the marshland along the shore of the Pamlico Sound in the Base area. Along the

backside of the creek marshes were also filled in with the dredged sand. The creek had

been dredged partway in from the ditch in 1933 and again in 1939, so that bigger boats

could get into the stores and fish houses.

The US Navy Base was constructed

in the area around the Coast Guard Stations in the village and was started in May or

June 1942. The Base was commissioned on October 9, 1942. The creek needed to be dredged

for use by the Navy while building the Navy Section Base. Some of the sand was used to

fill the marshland along the shore of the Pamlico Sound in the Base area. Along the

backside of the creek marshes were also filled in with the dredged sand. The creek had

been dredged partway in from the ditch in 1933 and again in 1939, so that bigger boats

could get into the stores and fish houses.

The Navy proceeded to build the first concrete road on the island. Called Ammo Dump Road, it ran from the Base along the waterfront on the North side of the creek (Silver Lake) turned left and followed what is now called British Cemetery Road. It made a right on present day Back Road and ran to where the fire house was located, to the left of where the Library now is. It then turned left and proceeded to the tee intersection. This entire section of land ran to the left and right to the Pamlico Sound shore. Inside the Ammo Dump there were several smaller road spurs that ran to the various ammo buildings. There were a couple of forty feet by twenty feet, one story buildings, with concrete foundations and sand banked against the sides and back. The entire road was just wide enough for one vehicle. The gate blocked the raod about 150 feet before you got the tee intersection.

The Ammo Dump was situated on forty seven acres of land owned by Isaac Willis O’Neal (Big Ike) and Martha Helen Williams O’Neal. The land was leased by the Navy for $5.00 for the duration of the war. The entire 47 acres was surrounded by a high cyclone fence with several strands of barbed wire on top. There were armed guards at the gate on Ammo Dump road.

Below are some interviews that Earl O’Neal had with Islanders that were living here during the war.

“It would shake the houses and sometimes the explosions cracked the cisterns, damaged the sheet rock and plaster in some of the houses. I heard one young man say how terrible it was to be out there and watch those men jump off the burning tanker.” Blanche Howard Joliff.

The Empire Gem, On Jan. 5,

1942, a boat landed at the north end of Ocracoke Island with two fresh-faced Coast

Guard boys from Pennsylvania and Tennessee. Fate and an International Harvester

truck delivered Ted Mutro and Mack Womack to the village. They could hardly believe

their good fortune, having been led to believe they’d be spending the war at a

beach resort. But at the end of the 13 mile drive to the village, their excitement

turned to gloom.

The Empire Gem, On Jan. 5,

1942, a boat landed at the north end of Ocracoke Island with two fresh-faced Coast

Guard boys from Pennsylvania and Tennessee. Fate and an International Harvester

truck delivered Ted Mutro and Mack Womack to the village. They could hardly believe

their good fortune, having been led to believe they’d be spending the war at a

beach resort. But at the end of the 13 mile drive to the village, their excitement

turned to gloom.

Ted Mutro thought Ocracoke was “the last stop in civilization.” “In the village, curiosity got the best of me,” remembers Mutro. “I asked him (the driver), I says, ” Where’s the heart of town at?” I was right behind the Community Store. He says, “You’re right on the main drag now. Do you want to get out and look around?” I say’s, ‘No, I’ve seen everything.’ I went in the new station, went up in the tower. ‘Damn, I said, ‘this is an island!’ the chief said to me, ‘Where’d you think you were at, New York City?’ He said, ‘You think this is bad, you ought to go to Portsmouth. We have 12 men over there, no electricity, no nothing. Got 12 men over there, they come up once a week, get their groceries, kerosene and everything on Portsmouth Island there.'”

Womac and Mutro thought the only things they’d be fighting in the war on Ocracoke were mosquitoes and boredom. Three weeks into their assignment they found out otherwise. Just after dark on Jan 23, the Empire Gem nervously approached the Diamond Shoals light buoy. It was a dangerous time to be there. The British tanker, the largest in the world at the time, was loaded with over 10,000 tons of refined gasoline, one quarter of Great Britain’s daily consumption. But standing between the Empire Gem and English petrol pumps was the U-66. At 7:40PM, two torpedoes slammed into the starboard holds and ignited a hellish inferno. A frantic SOS was tapped out by the radio operator and was received at the Coast Guard station at Ocracoke. Mutro and Womac got their first trip into the war.

“We started out there,” remembers Mutro. “The wind started kicking up and everything. We found it all right, oil and everything burning out. You couldn’t get alongside of nothing like that because the water was burning. Then all we could do is just go around and around, hoping to pick up somebody alive,” Womac says. “It’s a terrible feeling. Especially when you see them jump overboard with flames on to ’em and know that they was goin’ into the fire just as quick as they hit. It really had a bad smell to it. It wasn’t all oil burning.” Fifty Five men died on the burning Empire Gem. Only Captain Broad and his radio operator were rescued by lifeboat from Hatteras Inlet Station. Womac and Mutro might have thought Ocracoke as the last stop in civilization, but compared to being a merchant seaman, the isolation, boredom, and mosquitoes on the island suddenly didn’t seem all that bad. In fact, their opinion would change so dramatically that more than 50 years later they would still be living on the island.

The Empire Gem, a British Tanker carrying 10,000 tons of gasoline, was torpedoed on the night of January 23, 1942, by a German U-boat, U-66, captained by Richard Zapp. There were only two survivors out of the crew of 57: Captain Francis Broad and Assistant Radio Operator Thomas Orrell.

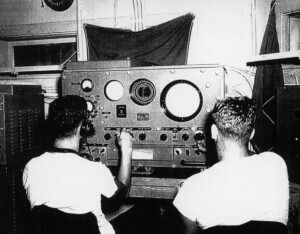

Various Images of the U.S. Navy on Ocracoke

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By October 1942, when the Base was completed, the Navy was already aware that the need for it had diminished, and by 1943 the Loop Shack was declared useless because the U-boat attacks had decreased. On January 16, 1944 the Base was converted to an Amphibious Training Base and in 1945 it became a Combat Information Center. In early 1946 the Base was closed and the boats returned to Little Creek, Virginia.

Story and facts courtesy Earl O’Neal

Previous Exhibits Below-

December Online Exhibit 2016 US Navy Base Ocracoke

November Online Exhibit 2016 Post Office

October Online Exhibit 2016 Dare Wright

September Online Exhibit 2016 Ocracoke School

August Online Exhibit 2016 Robbie’s Way

July Online Exhibit 2016 4th of July History

June Online Exhibit 2016 Hurricanes

May Online Exhibit 2016 Island Architecture

April Online Exhibit 2016 Charlie Ahman

March Online Exhibit 2016 Frank Treat Fulcher

February 2016 Online Exhibit Muzel Bryant

January 2016 Online Exhibit The Cochrans

December 2015 Online Exhibit JoKo Artist