One of the best-known

old style brick towers is the lighthouse at Ocracoke village on North

Carolina’s Outer Banks. Winslow Lewis lost the contract for this 65-footer

to Noah Porter, another New Englander. Porter’s work, completed in 1823,

has held up well over the years. The photo shows the two most characteristic

features of the old style design. The tower is bluntly conical, and the lantern

is somewhat off-center because it is positioned over the top of the spiral

stairway. The original birdcage lantern is gone, replaced by a

mid-nineteenth-century lantern having distinctive trapezoidal windowpanes. The

lantern was designed for a fourth order Fresnel lens installed in 1854; this

lens was replaced with another fourth order optic in 1895, and that lens remains

in use today. The tower’s brickwork was later covered with a stucco-like

mortar, painted white. Several other old style brick towers have received

similar treatments.

Origin of The Name

(The

following history is reprinted with permission from the East Carolina

University’s Ocracoke History website)

The exact derivation

of the name “Ocracoke” is unknown, though many suggestions have been

made. It has been suggested that the name is linked to the Algonquian word

“waxihikami” which means enclosed place, fort or stockade. On old

maps, the spelling varies from Wokokon, Woccocon, Occacock, Ocacoe, Ocacock,

Occacock, Ocreecock and now Ocracoke. A more far-fetched suggestion is that

Blackbeard the Pirate, waiting for the fateful dawn of November 22, 1718, prayed

in vain “O Crow Cock! O Crow Cock!” in hopes of escaping his

pursuers. A good primer on island names can be found at Philip Howard’s Ocracoke

Newsletter Website.

The Outer Banks along the coast of North Carolina is a

string of islands defined by inlets connecting the Atlantic Ocean on the east

with the sounds which extend in places as much as thirty miles westward toward

the mainland. These inlets have shifted over time; some have closed entirely,

new ones have opened, some have migrated along the islands and their depth

continually changes due to the vagaries of weather and current (Newell 1987:1).

The shifting depth and width of these inlets hindered maritime activity. Only a

few of the many inlets were deep enough to admit the passage of moderate-sized

vessels into the sounds. These inlets included Roanoke, Currituck, Topsail and

Ocracoke. Roanoke and Currituck were frequently used during North

Carolina’s early history, but became too shallow to admit any but the

smallest vessels by the 1730’s. Topsail Inlet had achieved some importance

by this time, but poor transportation connections with the interior limited the

growth of its commerce. With the exception of the region served by the Cape Fear

River, much of the colony’s commerce was channeled through Ocracoke Inlet

(Newell 1987:1).

The Outer Banks along the coast of North Carolina is a

string of islands defined by inlets connecting the Atlantic Ocean on the east

with the sounds which extend in places as much as thirty miles westward toward

the mainland. These inlets have shifted over time; some have closed entirely,

new ones have opened, some have migrated along the islands and their depth

continually changes due to the vagaries of weather and current (Newell 1987:1).

The shifting depth and width of these inlets hindered maritime activity. Only a

few of the many inlets were deep enough to admit the passage of moderate-sized

vessels into the sounds. These inlets included Roanoke, Currituck, Topsail and

Ocracoke. Roanoke and Currituck were frequently used during North

Carolina’s early history, but became too shallow to admit any but the

smallest vessels by the 1730’s. Topsail Inlet had achieved some importance

by this time, but poor transportation connections with the interior limited the

growth of its commerce. With the exception of the region served by the Cape Fear

River, much of the colony’s commerce was channeled through Ocracoke Inlet

(Newell 1987:1).Revolutionary Period

Throughout the American Revolution, British vessels and

privateers made numerous raids at Ocracoke Inlet, with several attempts to

blockade the inlet against all vessels sustaining the Patriot cause. These

activities led to the establishment of American land and naval forces at the

inlet, which continued to serve as a crucial artery of supplies until the

struggle for independence was won.

War of 1812

Throughout the War of 1812, Ocracoke Inlet served as a

base of operations for privateers and as an important avenue for supplies bound

for southeastern Virginia through the “back door.” An enemy attack

on the area had been feared since the beginning of hostilities, and in the

summer of 1813 the British made their appearance in considerable force: At

daybreak, July 12, the residents of Portsmouth, Ocracoke and Shell Castle awoke

to find a formidable British fleet anchored just off the Bar, including nine

large war vessels. Barges soon put off from the ship – one observer

counted nineteen barges, each carrying forty men – and when they entered

the inlet they attacked two American privateers, the Anaconda and the Atlas, and

a revenue cutter, capturing the privateers and forcing the cutter to retreat up

the sounds. Then the British troops landed at Portsmouth and Ocracoke, collected

hundreds of cattle and sheep, and after five days on the Banks weighed anchor

and sailed away, announcing before their departure that the entire coast of

North Carolina was under blockade (Dunbar 1958:39,150). Admiral Cockburn,

commander of the British naval force, had initially planned to proceed up the

Neuse River and capture New Bern. The escape of the revenue cutter to New Bern,

however, removed the necessary element of surprise, and the proposed attack was

abandoned. This was to be the only British incursion into the area of Ocracoke

Inlet. When hostilities ceased, attention was directed toward methods of

improving the inlet as an artery of commerce (Dunbar 1958:39).

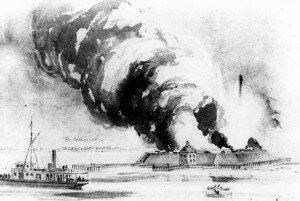

Soon

after the outbreak of the Civil War, Confederate forces seized the existing

forts along the coast of North Carolina and began construction of additional

fortifications on Roanoke Island and at Hatteras, Oregon and Ocracoke Inlets.

The Ocracoke facility was situated on Beacon Island, where an earlier

fortification had existed during the War of 1812. Of octagonal shape, the Civil

War installation was known alternatively as Fort Ocracoke or Fort Morgan. In

addition to a garrison there, it was reported that several hundred troops were

stationed at Portsmouth and on the beach below Ocracoke Inlet. All told, there

were about 500 Confederate troops in the area (Rush 1914:80). For more

information on Fort Ocracoke and during the Civil War, please check out the

SIDCO site

Ocracoke Brogue

Because of its

isolation, Ocracoke speech patterns have taken on a unique dialect, or

“brogue“, and

expressions over the past 250 years. Ocracoke brogue is the famous local

dialect. To some of the native islanders, there are only two kinds of people in

the world: O’Cockers and dingbatters (natives and non-natives,

respectively). For more information, click on the link above which will take you

to the Ocracoke Linguistics site of the North Carolina Language and Life Project

at the North Carolina State University.

Brogue Room

The

permanent exhibit in the OPS Museum, complete with continuous play video,

reflects the on-going research of Walt Wolfram, a North Carolina State

University linguist and self-described “wampus cat” (that’s

O’Cocker for someone abnormal!).

The

existence of the Navy and Coast Guard installations on Ocracoke during World War

II brought numerous servicemen from outside the area and had an invigorating

effect on the local economy. Ocracoke prior to the war was seeing approximately

3,000 visitors each summer to fish and swim, while another 500 visitors flocked

to the island each fall and winter for duck hunting (United States Congress

No.325:6). The establishment of Cape Hatteras National Seashore in 1953 brought

a steady flux of outsiders. Restricting the flow of tourists were the

difficulties in reaching the island and the lack of roads on the island itself.

These impediments were eliminated in 1957 with the creation of the state’s

establishment of year-round, toll-free ferry service across Hatteras Inlet, and

the completion of a paved road between Ocracoke Village and the ferry

terminal.

Since 1953 all of Ocracoke Island,

with the exception of Ocracoke Village, has been under federal ownership as a part

of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore, administered by the National Park Service.

The island remains unspoiled and in its natural state, the only improvements being

the state road and about ten miles of sand-fence barrier.

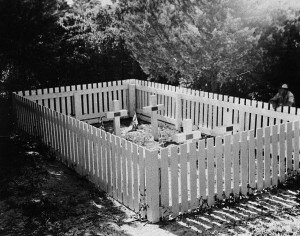

The

tiny British graveyard on Ocracoke Island contains four graves, two of which are

marked “Unknown.” A third bears the name of Lt. Thomas Cunningham,

and the fourth that of Stanley R. Craig, A.B. The words “Royal Navy”

and “Body found May 14, 1942” are inscribed on all four of the

bronze plaques on concrete crosses erected at the time of burial. All bodies are

identified as members of the crew of HMS Bedfordshire which disappeared with all

aboard en route from Norfolk to Morehead City, its temporary “home”

port. Rites at Ocracoke were held by the late Amasa Fulcher, prominent layman of

the local Methodist Church. A year later, at Mrs. Cunningham’s request, a

Catholic service was held by the Navy chaplain, then stationed at Ocracoke. Land

for the British burials was given by Mrs. Alice Wahab Williams near the Williams

family graveyard. Markers were made by the T.A. Loving Construction Co., then

building the Navy base nearby. A commemorative service

is held each year in May.

If you would like more information on Ocracoke please see Ocracoke Village Site and Ocracoke Navigator